.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Europe’s Affordable Housing Plan: Essential for young workers and the EU at large

The EU’s Affordable Housing Plan is a first step towards tackling the housing crisis, which disproportionately affects young workers across Europe.

Looking back, moving forward | Editorial of SG Klaus Heeger

CESI SG Klaus Heeger reviews major political and social developments at the close of the year and looks ahead with confidence to the challenges of 2026.

Conference on equality policies in Spain

CESI, with the support of its Spanish member CSIF, organised a conference in Madrid to discuss EU gender equality policies and their implementation in Spain.

Urgent call by European civil society to the European leaders and the leadership of the EU

As a proud member of the European Movement International (EMI), CESI fully supports the urgent call to defend democracy, uphold fundamental rights and the rule of law, and strengthen the EU’s capacity to act in the face of geopolitical challenges.

The EU Green Deal and Automotive Package: Competitiveness alongside innovation

A responsible EU Automotive Package under the Green Deal is needed to safeguard jobs, industry and Europe’s competitiveness.

eQualPRO in Poland: Advancing gender equality in the digital age

CESI organised a national conference in Poland under the eQualPRO project, focusing on gender equality in the context of digitalisation and artificial intelligence, with the support of its Polish member WZZ.

Quality Jobs Roadmap: Time to deliver

CESI welcomes the Quality Jobs Roadmap and calls for binding action and tough enforcement to turn it into real gains for workers.

New year, new leadership for CESI Youth

CESI thanks Matthäus Fandrejewski for twelve years of dedicated leadership of CESI Youth and welcomes Antonello Pietrangeli as its new Youth Representative, opening a new chapter for youth representation in CESI.

Spain: CSIF achieves pay rise and reforms

CESI member organisation CSIF has secured a retroactive 2025 pay rise for Spain’s public-sector workers and a multi-year wage deal through 2028. The agreement totals an 11.4% increase and includes wider improvements to working conditions and public services.

FISMIC-CONF.S.A.L. joins CESI

The Italian metal workers trade union FISMIC-CONF.S.A.L. has joined CESI.

End violence against women!

On 25 November, CESI joins organisations worldwide in marking the annual International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.

Hearing on the application of the Working Time Directive (WTD) in the armed forces

At a high-level hearing organised by the European Commission (DG EMPL and DG DEFIS), CESI presented its views on the application of the Working Time Directive (WTD) to military personnel across the European Union.

Develop EU Military Mobility with military staff and workers

According to CESI, the newly presented EU Military Mobility Package needs to be deployed together with military and civilian staff in the armed forces.

Romain Wolff at the DBwV General Assembly

At the re-election of André Wüstner, the President of CESI highlighted the strong CESI–DBwV partnership and stressed that Europe must strengthen its defence capabilities without undermining social standards or the welfare state.

CESI@noon: Tackling health care workforce crises

Yesterday, CESI held a CESI@noon debate on the European Parliament's forthcoming own-initaitive report on an EU health workforce crisis plan.

A turning point: Why the CJEU’s minimum wages ruling matters

By upholding the Minimum Wages Directive, the CJEU has set a clear signal: fair wages and strong collective bargaining are central to Europe’s social future. The judgment empowers governments to lift wage floors and tackle in-work poverty with renewed confidence.

EU Equal Pay Day 2025: A long way to go

On Equal Pay Day 2025, CESI recalls that the gender pay gap in the EU still stands at an unacceptable 12%.

Towards equal opportunities in defence employment

On 4 November 2025, CESI’s Security and Defence Commission and the eQualPro conference brought together experts in Berlin to discuss how to strengthen gender equality in Europe’s armed forces.

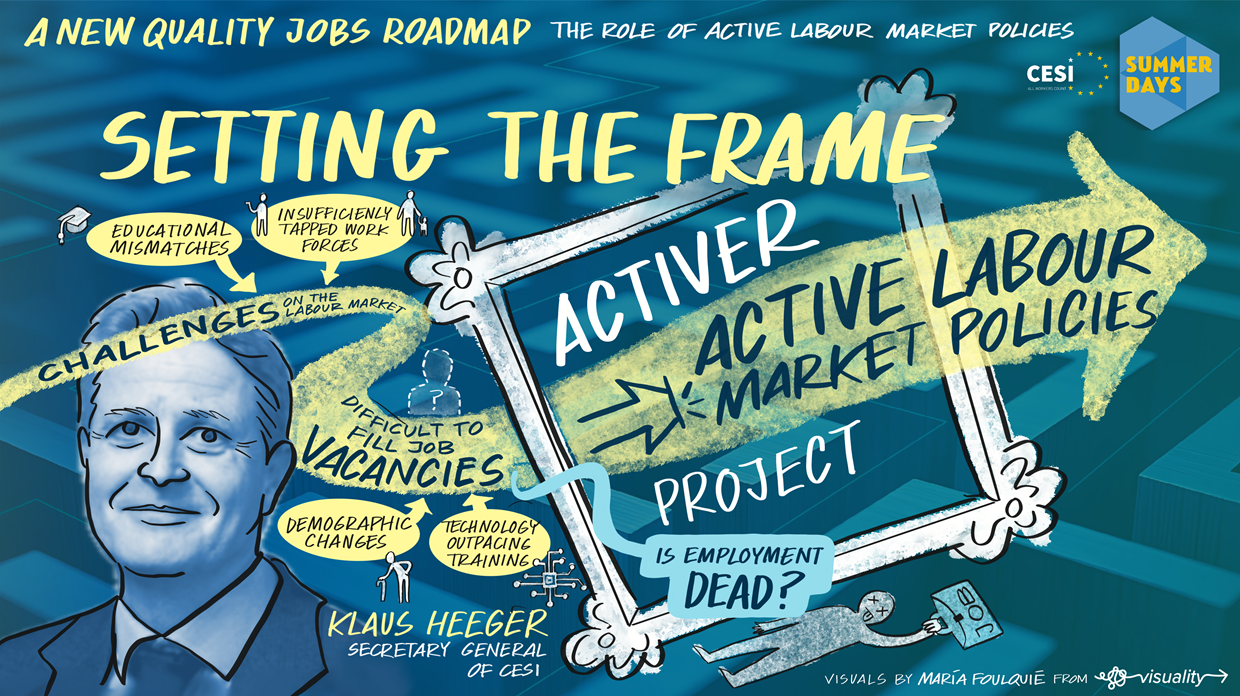

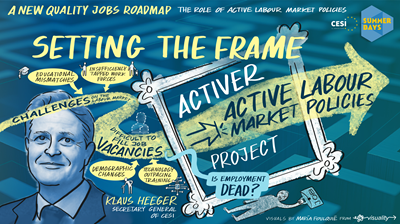

Activer project closes with position on trade union priorities on active labour market policies

CESI's Activer project closed with the adoption of a new position paper on trade union priorities for successful active labour market policies.

New position on AI at work

At its last meeting of the year, CESI's Presidium yesterday adopted a new position on AI at work.

Minimum Wages Directive stands: A clear mandate for fair pay

Brussels, 11 November 2025 — CESI welcomes today’s Grand Chamber judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union confirming the validity of the EU Directive on Adequate Minimum Wages.

CESI Seniors hold constitutive meeting

On November 5, the newly established CESI Seniors held their constitutive meeting.

CESI at the SEISMEC General Assembly in Thessaloniki

CESI joined partners in Thessaloniki for the SEISMEC General Assembly to discuss progress on promoting human-centric, ethical, and socially sustainable innovation in industry.

Digital sovereignty and people’s abilities

Editorial by Klaus Heeger, CESI Secretary General

Expert Commission ‘Post and Telecoms’ sets positioning on new EU Delivery Act

At its annual meeting today in Brussels, CESI’s Expert Commission set its position an announced new EU Delivery Act which will replace or amend the current EU Postal Services Directive and Cross-Border Parcel Deliveries Regulation.

European Commission work programme for 2026: Time to focus on socially sustainable competitiveness

CESI welcomes several new initiatives that the European Commission has announced to drive forward in 2026, but misses at least one.

CESI in line with the priorities of the Council of Europe Conference of International NGOs

This week, from October 13-16, the Council of Europe (COE) held its latest annual session of the ‘Conference of International Non-Governmental Organisations’ in Strasbourg, aimed at giving space to democratic values, civic participation and social rights across Europe.

CESI@noon on affordable housing in the EU

A timely event on affordable housing in the EU – building a social Europe for all in line with the objectives of the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR).

EU Defence Readiness Roadmap 2030 must be rolled out with the military & civilian personnel of the armed forces

Today, the European Commission published a new Defence Readiness Roadmap 2030, in an effort to secure Europe’s defence preparedness by the end of the decade. CESI argues that all defence policy initiatives must be prepared and implemented together with those that execute operations: the military & civilian personnel of the armed forces.

EU postal services social dialogue seminar in Athens

On October 7 CESI took part in a European social dialogue project seminar in Athens, together with UNI Europa and PostEurop, on 'Skills and work environment in the digital postal transition'.

CESI@noon: Tackling EU health workforce shortages through the EPSR

A CESI@noon event, held in the frame of CESI’s PillACT project, exploring how the European Pillar of Social Rights can help address the EU’s growing healthcare workforce shortages.

CESI and ANPE call for stronger implementation of European equality policies in education

In Barcelona, CESI and ANPE, through the EqualPro project, called for stronger implementation of European equality policies in education.

CESI welcomes European Parliament endorsement of a revised EWC Directive

CESI welcomes today’s vote of the European Parliament to approve a trilogue agreement with the Council on a revised European Works Councils (EWC) Directive.

CESI calls for a right to disconnect and fair telework

On the occasion of a second phase social partner consultation, CESI calls on the European Commission to table legislation on a right to disconnect and fair telework.

Encouraging European Parliament vote to enter trilogues on a traineeships directive

This week, the European Parliament formally voted to enter into trilogue negotiations with the Council to adopt a new EU Traineeships Directive - a step to end abusive employment among young persons in Europe.

Celebrating EU’s teachers: CESI calls for more investments in education

At a time when teacher shortages, low salaries and unsustainable workloads threaten Europe’s education systems, EU educational leaders and CESI teacher representatives gathered yesterday in Brussels in the European Parliament for an ‘Honouring the Teaching Profession in Europe’ event.

One year after the Draghi report: Build competitiveness together with workers

A high level conference yesterday in Brussels discussed how Europe can secure its economic competitiveness in the light of increasing global competition. According to CESI, competitiveness must be achieved together with workers and unions, not on their back.

CESI reaction to the 2025 State of the Union

It is time to turn high-level announcements into tangible improvements for people’s lives, in workplaces, in public services, and in the armed forces.

CESI speaks in European Parliament Intergroup on Civil Protection on working conditions of firefighters

On September 9, CESI was invited by the European Parliament’s Intergroup on Resilience, Disaster Management and Civil Protection to contribute expertise from its firefighter staff unions.

EqualPro conference in the European Parliament in Strasbourg on EU women’s rights policies

On September 9, CESI in cooperation with MEP Grégory Allione (Renew), held a high-level conference in the European Parliament in Strasbourg on ‘European equality policies made in Brussels: What added value for France?’

Honouring the teaching profession in Europe

Breakfast hearing at the European Parliament hosted by MEP Hristo Petrov, Vice-Chair of the Committee on Culture and Education

EqualPro conference on EU gender equality policies in Strasbourg on September 9

On September 9, CESI will hold an EqualPro project conference on EU gender equality in the European Parliament in Strasbourg.

New position on the implementation of the European Pillar of Social Rights

CESI adopted a new position on the implementation of the European Pillar of Social Rights.

From our Summer Days to a busy September | Editorial of SG Klaus Heeger

"That is what we will do this month - together with you."

CESI affiliates Synnöve Nüchter and Eva Fernández Urbón elected into EWL Board of Administration

At the General Assembly of the European Women’s Lobby (EWL) on June 7-8, CESI’s affiliates Synnöve Nüchter and Eva Fernández Urbón were elected into the EWL's Board.

New position on a new EU gender equality strategy

As part of a consultation on a new EU Gender Equality Strategy 2026-2030, CESI issued a new position on priorities for improved women's rights and equal opportunities in Europe.

Women, public employment and artificial intelligence

On 14 July 2025, CESI organised a conference in Terrasini (Palermo) to discuss the impact of artificial intelligence and digitalisation on gender equality in the public sector, highlighting challenges, best practices and the key role of social partners in promoting fair and inclusive workplaces.

MFF 2028-2034: The EU needs the means to deliver

CESI Secretary General Klaus Heeger generally welcomes the European Commission’s publication of its proposal for the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 2028-2034 yesterday.

CESI Youth Congress in Vilnius elected its new leadership!

Congratulations to CESI’s newly elected Board: Youth inclusion in action begins now!

ACTIVER conference in Vilnius on youth employment

On July 11, CESI held a successful ACTIVER project conference on youth unemployment and active labour market policies in Vilnius.

New CESI Europe Academy Board

On June 26 CESI's Europe Academy General Assembly elected a new Europe Academcy leadership.

ACTIVER conference: 'Youth unemployment and active labour market policies'

As part of the EU co-funded ACTIVER project, CESI aims to strengthen capacity and raise awareness of the vital role that workers, trade unions, and social partners play in shaping and implementing effective active labour market policies in today’s era of permacrisis.

PillAct: From Dialogue to Action

PillAct reflects a clear European commitment to securing a fairer future for all.

#ActiverCampaign: Trade Unions in Action

The campaign is part of CESI’s EU-funded Activer project, aiming to strengthen Active Labour Market Policies across Europe by highlighting the crucial role of trade unions and social partners in building fair and resilient employment systems.

French CFE CGC Public Service Federation becomes a member of CESI

At its statutory meeting on June 26, the Board of CESI endorsed the membership application of the French CFE CGC Public Service Federation to join CESI.

CESI Summer Days 2025: Active labour market policies for new EU Quality Jobs Roadmap

In the face of rapid labour market transformations, CESI held its fifth Summer Days on June 26-27 in Brussels, on active labour market policies in Europe.

In memory of Ulrich Silberbach- A tireless advocate for public services and social justice

It is with deep sorrow that we share the news of the passing of Ulrich (Uli) Silberbach who died on June 25, 2025, at the age of 63.

CESI and WZZ host seminar on active labour market policies

CESI and WZZ ‘Forum – Oświata’ held a timely seminar in Poland on 13 June 2025, discussing active labour market policies and the key role of unions in building sustainable employment.

Celebrating World Public Service Day 2025

Public sector investment and social partnerships as pillars of resilient and competitive societies

This week: CESI Summer Days 2025 on active labour market policies

Register now for CESI's 5th annual Summer Days on June 26/27 in Brussels.

Resolution now available on reconciling defence spending and investments in people

At its meeting on June 18, the Presidium of CESI adopted a resolution on a reconciliation of necessary defence spending and much-needed investments in people.

New position on public procurement rules in the EU

On June 19, the Presidium of CESI adopted a new position on a foreseen revision of EU public procurement rules.

New consultation contribution on the forthcoming EU Quality Jobs Roadmap

On June 18 the Preidium of CESI adopted policy priorities for a new EU Quality Jobs Roadmap.

A New Quality Jobs Roadmap for Europe

Editorial by Klaus Heeger, Secretary General of CESI

Hearing with the European Commission on the future of the automotive industry

Today CESI participated in a hearing with the European Commission on change management in the automotive industry in Europe.

CESI hosts train driver lobby days for its member ALE

On May 20-21, CESI hosted train driver lobby days in Brussels for its member ALE, the Federation of European Train Drivers' Unions.

Open call for tender: 'The postal sector - an inclusive employer'

The European social partners for the postal sector - PostEurop, CESI and UNI Europa - are looking for a consultancy to support their EU co-funded project 'The postal sector: an inclusive employer for a more inclusive society'.

CESI Commissions on Employment and Gender Equality elect new leadership

At its constitutive meeting on May 16, following CESI's Congress in December, CESI's Commissions on Employment and Social Affairs (SOC) and Women's Rights and Gender Equality (FEMM) elected their new leadership.

EqualPro conference in Berlin on the added value of EU gender equality policies in Germany

On May 16, CESI hosted an EqualPro project conference in collaboration with its member dbb, the German civil service federation, in Berlin.

CESI in Belgrade: Strengthening gender equality in Serbia and the healthcare sector

On May 8th, 2025, CESI marked a landmark moment for healthcare trade union cooperation, gender equality, and Serbia’s EU integration in Belgrade.

CESI: New EU public procurement rules must be socially fair

In response to an ad-hoc European social partner consultation, CESI has called for new public procurement rules to be socially balanced.

CESI publishes priorites for next EU Multiannual Financial Framework 2028-2034

On May 5, CESI published its priorites for the EU's next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF).

Violence is not part of the job!

CESI SG Klaus Heeger co-signed the updated European guidelines to protect workers from third party violence and harassment.

Strengthening ALMPs and European cooperation: ACTIVER seminar in Romania

CESI, Uniunea TESA and CSN Meridian brought together experts from across Europe to strengthen social dialogue and cooperation for fair wages and active labour market policies in the public health sector.

CESI on World OSH Day: Put digitalisation and AI in the spotlight

Today, on the occasion of this year's annual World Day for Safety and Health at Work, CESI reaffirms its commitment to promoting occupational safety and health for all workers.

CESI@noon on trade union perspectives on housing, gender & precarious work

As part of its EU co-funded eQualPRO project, CESI held a timely event on the intersection of housing, gender inequality and precarious employment.

Gender equality in public administration: A CESI debate in Rome

On April 9, 2025, CESI hosted an eQualPro event in the liaison office of the European Parliament in Rome, focusing on gender equality in public administration.

CESI participates in social partner kick-off on EU Quality Jobs Roadmap

Today, CESI Secretary General Klaus Heeger participated in a high-level kick-off meeting on a new EU Quality Jobs Roadmap with EU Jobs Commissioner Roxana Mînzatu.

Activer event in Italy: Unions driving skills and inclusion

At the #ACTIVER event in Salerno, trade unions advanced strategies for skills, inclusion, and fair transitions.

From reception to reconstruction – New study by the European Policy Centre and CESI

A new study in the context of CESI's 'Activer' project sheds light on the evolving labour inclusion of displaced Ukrainians.

CESI at SEISMEC to share trade union views on human-centric ICT at work

On April 7/8, CESI participated at the SEISMEC project's most recent General Assembly in Cork to present trade union priorities for human-centric ICT in workplaces.

Strengthening equality and union partnership in Riga

By focusing on past EU achievements, present obstacles, and future risks, CESI aims at helping workers and unions be agents of fairness and change.

Tariffs, tensions, and the cost to workers: CESI on the U.S. trade measures

Trump’s tariffs risk a trade war that threatens jobs, fuels inflation, and hits workers hardest. CESI urges a united EU response to protect our industries and social model.

CESI welcomes the EU's new Internal Security and Preparedness Union Strategy

CESI welcomes the EU Internal Security Strategy and the Preparedness Union Strategy as important milestones toward safeguarding the Union and its people from an increasingly complex landscape of threats.

OPINION | Public services and social dialogue: Europe's competitive advantage

CESI SG Klaus Heeger emphasises that social dialogue and public services are Europe's competitive advantage, not obstacles to growth.

CESI urges socially sustainable competitiveness agenda for Europe

As the European Commission moves ahead with a policy agenda of deregulation, CESI has adopted a new resolution to call for a socially sustainable competitiveness agenda for Europe.

Joint letter: CESI supports call on the European Commission to give space to ambitions on long-term care

Today, together with 20 European civil society and trade union organisations, CESI supports a joint call on the European Commission to give space to ambitions on long-term care. A corresponding letter was transmitted to the European Commissioner for Social Rights and Skills, Quality Jobs and Preparedness, Roxana Mînzatu.

Defence – A third transition underway, after the green and the digital?

CESI broadly welcomes the new EU White Paper on European Defence, published by the European Commission on March 19. It could lead to a new third major transition after the green and the digital.

Τhe role of trade unions in affordable housing, gender equality, and tackling precarious work

In times of increasing housing prices, and thus housing scarcity, those facing homelessness or housing difficulties are often either unemployed or in precarious, low-wage employment. Within this group, women and single mothers make up a considerable share, due to either unemployment, precarious employment or low wages.

CESI calls on social outcomes as priorities in revised EU public procurement rules

In a consultation statement, CESI has called on the European Commission to make social outcomes a priority in revised EU directives on public procurement and concessions.

International Women’s Day: CESI welcomes new EU Roadmap for Women’s Rights

CESI underscores that the success of the Roadmap will depend on continued collaboration between the European institutions, Member States, social partners and civil society.

SynCrisis: Strengthening public services for a resilient Europe

CESI's SynCrisis campaign calls for urgent investment in public services to build resilience, protect workers, and ensure fair access to quality healthcare, education, and social support.

‘ReArm Europe’: A Paradigm Shift in European Defence and Societal Resilience

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen couldn’t have been blunter. In her letter to the special European Council she wrote: “A new era is upon us. Europe faces a clear and present danger on a scale that none of us have seen in our adult lifetime”.

March 3 – European Day for a Work-Free Sunday

Ensure synchronised resting time also in times of competitiveness

The European Employment and Social Rights Forum and the proposed “Union of Skills”

CESI Secretary General Klaus Heeger participated in the European Employment and Social Rights Forum 2025, Europe’s largest event on employment and social affairs, which took place on March 5-6 in Brussels.

CESI’s 8th European Defence Round Table (EDRT)

18 February 2025 2024 1:30 – 3:00 PM | online & in Brussels | In English & German languages.

The Polish EU Presidency: Delivering in times of uncertainty

Today, the Polish Prime Minister Tusk presented the priorities of the Polish Council Presidency to the European Parliament.

SynCrisis final conference: Strengthening public services in an era of ongoing crises

On December 13, the CESI EU co-funded SynCrisis project reached its culmination with a final conference, marking the conclusion of a two-year initiative focused on the essential role of public services in addressing Europe’s multifaceted and interconnected crises.

Empowering workers for the future

A mandate for the next five years | Editorial of CESI SG Klaus Heeger Under the theme “Independence, Unity, Progress: Empowering Today’s Workforce for Tomorrow,” the Congress gave us an opportunity to reflect on our achievements while also addressing the challenges ahead.

01 — 00

.png)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

What do we do?

In order to complement the activities of its Trade councils and Commissions, CESI will in 2025 focus its work on the following priority areas:

Socially friendly climate change and green transition

Employment- and gender-friendly digital transition

Public health and social investments

Ensuring well-being and security in changing work environments

Latest news

The Europe Academy is CESI’s internal training centre.

Each year, the CESI Europe Academy engages in usually two projects with financial support of the European Commission.

As a capacity-building instrument for trade unionists, these projects provide CESI’s members with the possibility to delve deeper into social, employment-related and political challenges in Europe and engage them in debates with policy-makers and international experts during dedicated seminars.

Get in touch

with us

Confédération Européenne des Syndicats Indépendants (CESI)

Contact form

Stay up to date

Don’t miss a thing and subscribe to our newsletter

Subscribe now and receive newsletters and much more!